At the beginning of the month, I asked Lexicide’s followers

this question:

I just read a news story referring to the Sword of Damocles. With the classics taught less and less in schools, do young people know what that is? How about the Augean stables? Achilles’ heel? Pandora’s box? Even “beware Greeks bearing gifts” assumes one knows the belligerents in the Trojan War.

What expressions — classical, Biblical, Shakespearean, etc — do you wonder will one day befuddle contemporary readers?

To my list, readers added Gordian knot, Oedipus

complex, and crossing the Rubicon.

But then quite a few readers chafed at the idea one had to be classically read to understand and use these phrases. Surprisingly, the pushback came from a published novelist, a high school English teacher, and a college professor of ancient texts. Others scoffed at my concern, claiming we as a culture might lose the die is cast or the labors of Hercules, yet we gain new signposts such as taking the red pill.

I may just have my nose in the air, but I think knowing the

source material makes these references richer and rounder in meaning – meaning which

is sometimes lost without knowing the origin. Take sword of Damocles.

Typically, writers use it to evoke a situation where danger could arise at any

moment. But the reason King Dionysius hung a sword over his throne was to show his

subject Damocles how tenuous his position was – that even though he was a great

and wealthy king, enemies lurked behind every corner. So it’s not just an

illustration of impending danger, but one caused by a station many regard as enviable.

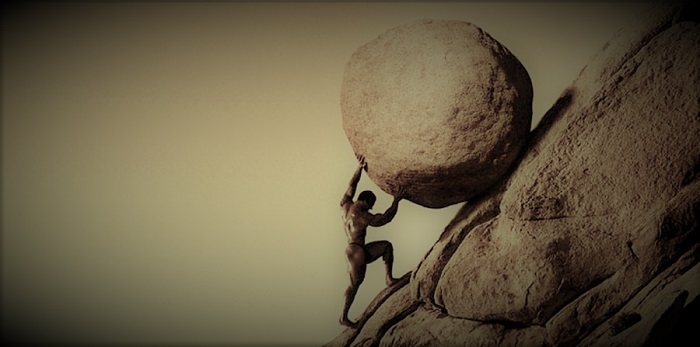

People wash their hands of a problem to absolve themselves of responsibility. But did Pilate’s washing achieve this? (Anyone who recites the Apostle’s or Nicene Creed on Sunday would answer “no!”). And a Sisyphean task is not simply any vexing, annoying job. It’s one you must repeat over and over with nothing to show for it. The image of repeatedly muscling a massive boulder uphill only to watch it roll back down is much more evocative than simply confronting a difficult deliverable.

(Plus, dammit, these stories are just fun. The Aeneid and The Odyssey remain some of the most rousing adventures in print. Without their foundations, Percy Jackson and Wonder Woman, not to mention Lord of the Rings and the Legend of Zelda, wouldn’t have been worth their authors’ attention.)

What say you? Have you ever leveraged your liberal arts education on a masterful literary reference, only to be met with blank stares? If that isn’t cleaning the Augean stables, I don’t know what is.

See also Splitting the baby