A few days ago, I reported on reader CLG’s (aka Cliggie Smalls) brush with timely used as an adverb. Her friend Elizabeth joined in the rant:

There is a related word of which I have an irrational hatred. It just sounds wrong. I first learned of its existence when I was still working in NY — my idiotic manager used it in a memo and I was convinced she was making it up (or at best, using her automatic Word synonym generator) since she used to have a very strange use of language in general.

That word is timeous.

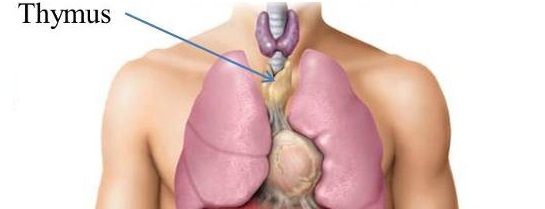

Never heard of it? If you’re on the Yankee side of the pond, you probably haven’t. According to the OED, it’s Scottish in origin. And it’s pronounced time-us, kind of like the gland.

Here’s where it gets interesting. Commenter Ruth on Gaertner-Johnston’s blog (to which I referred in the timely article) says of timeous:

I thought you might be interested to know that we use it fairly regularly in formal writing in South Africa (we generally follow the British style of English). The document I’m currently working on reads that my company “requires timeous notification of …”

Indeed, Merriam-Webster adds South Africa to the short list of localities that employ the word. Please note, though, that timeous is not an alternative to timely as an adverb. Like timely, timeous is an adjective, with timeously being the adverb form.

I encourage you to read all the comments on the Lynn Gaertner-Johnston’s Business Writing article on timely. You will also note that the use of timely as an adverb is archaic, so unless you’re writing writs of marque and reprisal, just knock it off.

— Otto E. Mezzo

See also: Timely

References: http://www.businesswritingblog.com/business_writing/2007/01/timely_or_on_ti.html

https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/timeous

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/timely