Facebook. It’s for old people, so my teenaged son tells me. It’s so senior-oriented, in fact, it offers a feature called Memories. See what you posted one year ago, two years ago, ten years ago – because of course you don’t remember. I SAID, “YOU DON’T REMEMBER!”

But sometimes Memory Lane is a great place to be. Last January, I solicited suggestions for your favorite false etymologies – backronyms, folk etymologies, etc. Well, I never got any, so I let the issue drop (and nursed no hurt feelings, I swear). But I shouldn’t have, because while no one commented on the website or on Lexicide’s Facebook page, quite a few of you added comments on my personal MyFace page. Thanks to Memories, they came back to me last week!

Let’s start with D.C. Dave, who offered up two false etymologies linked to people: nasty and crap. Nasty supposedly originated with political cartoonist Thomas Nast (who invented the Republican elephant and Democrat donkey, in addition to the caricature of Uncle Sam we know so well). Not true – the word long pre-dated the 1800s, when Nast employed his cutting, nasty wit. Likewise, crap comes to us from the Dutch krappe, not the toilets promoted by Thomas Crapper.

Dave also pointed out that butterfly is in no way a confusion of flutter-by. Thanks to L.A. Scott for reminding us this transposition of initial consonants is called a Spoonerism in honor of the Revered William Spooner, its most famous practitioner.

L.A. Scott then noted that Azusa does not derive from “Everything from A to Z in the USA.” While that was a promotional phrase used by the town’s Chamber of Commerce, the name comes from an ancient Amerindian place name. (Scott also claimed “his heart broke when [he] found out it was a retcon.” Here’s a tissue, Scott.)

Philly-based writer and frequent contributor Andrew had a slew for us: tip from “To Insure Promptness” (heard that one), posh from “Port Out Starboard Home” (also heard that one), and E. J. Korvette from Eight Jewish KORean war VETs. I had never heard of E. J. Korvette or the folk etymology, but Wikipedia and Snopes pointed me in the right direction.

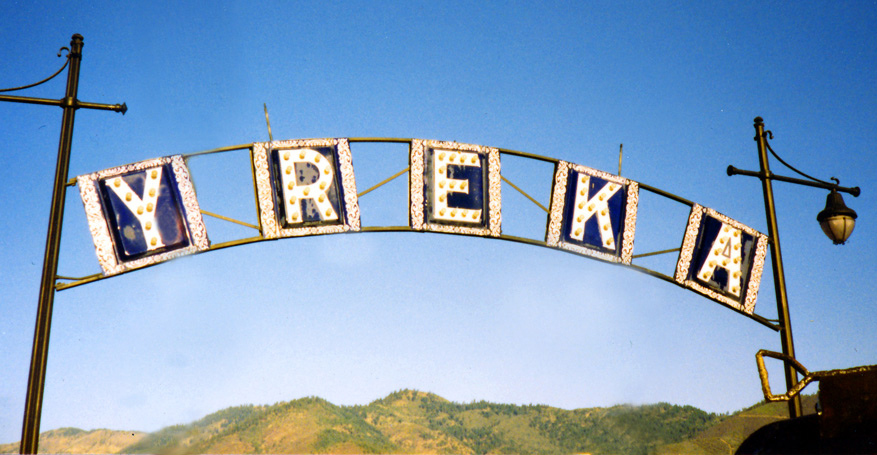

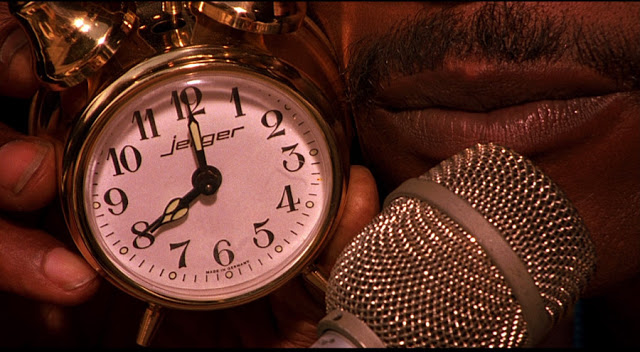

Riffing off Azusa, Andrew also chimed in that Yreka, California, did not originate with the word BAKERY read in reverse, Mark Twain’s claim notwithstanding. Also that 2001: A Space Odyssey’s* HAL 9000 was not so named because the letters HAL directly precede IBM by one alphabet space. I had heard that one and it never made sense. If HAL is the descendant of IBM, shouldn’t it be the JCN 9000? Anyway, HAL is a contraction of Heuristically programmed ALgorithmic computer. That comes straight from Arthur C. Clarke. Take it up with him.

To finish, Airworthy Andy the Floridian pilot reminded Christians and non-Christians alike that IHS never stood for “In His Steps” or “In His Service,” as some claim (the Him being Jesus of Nazareth). The Christogram IHS long pre-dates modern English anyhow – the early Christians used IHS as a shortened form of Jesus’ Greek name, ΙΗΣΟΥΣ (S being the Latin form of the Greek letter sigma). And yes, this is likely where the blasphemous utterance “Jesus H. Christ” originates.

So our thanks for all your contributions, only a year late. Ah, Memories!

– Otto E. Mezzo

*Does it seem weird to write about the events in 2001: A Space Odyssey in the past tense, since 2001 is, like, seventeen years ago? Yes. Yes, it is.